Shopping cart

Your cart empty!

Terms of use dolor sit amet consectetur, adipisicing elit. Recusandae provident ullam aperiam quo ad non corrupti sit vel quam repellat ipsa quod sed, repellendus adipisci, ducimus ea modi odio assumenda.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Sequi, cum esse possimus officiis amet ea voluptatibus libero! Dolorum assumenda esse, deserunt ipsum ad iusto! Praesentium error nobis tenetur at, quis nostrum facere excepturi architecto totam.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Inventore, soluta alias eaque modi ipsum sint iusto fugiat vero velit rerum.

Sequi, cum esse possimus officiis amet ea voluptatibus libero! Dolorum assumenda esse, deserunt ipsum ad iusto! Praesentium error nobis tenetur at, quis nostrum facere excepturi architecto totam.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Inventore, soluta alias eaque modi ipsum sint iusto fugiat vero velit rerum.

Dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Sequi, cum esse possimus officiis amet ea voluptatibus libero! Dolorum assumenda esse, deserunt ipsum ad iusto! Praesentium error nobis tenetur at, quis nostrum facere excepturi architecto totam.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Inventore, soluta alias eaque modi ipsum sint iusto fugiat vero velit rerum.

Sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Sequi, cum esse possimus officiis amet ea voluptatibus libero! Dolorum assumenda esse, deserunt ipsum ad iusto! Praesentium error nobis tenetur at, quis nostrum facere excepturi architecto totam.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Inventore, soluta alias eaque modi ipsum sint iusto fugiat vero velit rerum.

Do you agree to our terms? Sign up

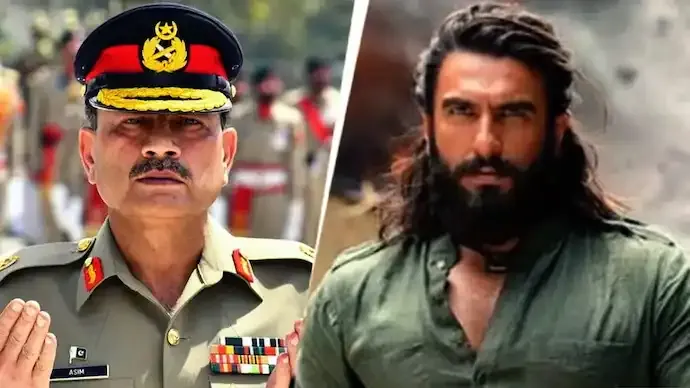

Pakistan’s military chief Asim Munir is reportedly focused on strengthening his country’s defences against another possible Indian retaliatory strike. His shopping list includes advanced Chinese fighter jets and missile defence systems meant to counter weapons such as India’s BrahMos. But there is one weapon he cannot intercept — a Bollywood blockbuster that has begun reshaping public narratives on Pakistan’s deep state.

That weapon is Dhurandhar, directed by Aditya Dhar. Released just months after Operation Sindoor, the film tells a fictional yet meticulously researched story of an Indian sleeper agent operating within Pakistan, striking at the heart of the country’s military–terror nexus.

Set against the backdrop of Pakistan’s covert war against India and the Karachi underworld of the early 2000s, the film draws inspiration from real figures such as Rehman Dakait, Uzair Baloch and Arshad Pappu, whose links with Pakistan’s security establishment have long been documented.

Blending elements reminiscent of Satya, Company, Fauda and Homeland, Dhurandhar has emerged as the highest-grossing Indian film of the year. While officially banned in Pakistan, it has reportedly become one of the most pirated films in the country, circulating widely through unofficial channels and embedding itself in popular culture.

The film directly challenges Pakistan’s long-standing strategy of state-sponsored terrorism under the cover of nuclear deterrence. It unapologetically endorses India’s right to retaliate against cross-border terror — a theme that resonates strongly with Indian audiences and, increasingly, with Pakistani viewers exposed to alternative narratives.

This is precisely why Dhurandhar unsettles Rawalpindi. The film strikes at what military theorists call the “centre of gravity” — not the military or political leadership, but the civilian mind space that Pakistan’s deep state has long sought to influence.

Munir is not the first Pakistani military ruler to be wary of Bollywood’s influence. Nearly two decades ago, former dictator Pervez Musharraf openly expressed discomfort over Indian films portraying Pakistan negatively. His anxiety stemmed from an understanding that cinema can shape public opinion more powerfully than official statements or propaganda.

The concern is rooted in classical military theory. Prussian strategist Carl von Clausewitz identified the people as one of the three pillars of a nation’s war-making capacity, alongside the government and the military. Pakistan’s strategy has historically targeted India’s political leadership and armed forces while simultaneously attempting to influence Indian public opinion through narratives of “peace” and moral equivalence.

For years, this approach found indirect support in sections of popular culture. Several earlier films portrayed terrorism as a product of circumstance rather than state policy, often omitting the role of Pakistan’s military establishment. Dhurandhar marks a clear departure from that trend.

Following Uri: The Surgical Strike, Dhurandhar pushes the cinematic lens further, directly calling out Pakistan’s deep state and its generals. The film’s upcoming sequel is expected to go even further, reportedly portraying senior Pakistani military figures as the architects of covert war against India.

This shift signals a broader change in Indian cinema — one less constrained by overseas market considerations and more willing to address uncomfortable truths. In doing so, Dhurandhar undermines years of carefully constructed narratives that sought to blur the line between terror groups and the Pakistani state.

For Asim Munir, the challenge is not the military message alone, but the erosion of narrative control. Missiles can be intercepted, airbases rebuilt, but once public perception shifts, it is far harder to contain. That is why Dhurandhar may prove more unsettling for Pakistan’s military leadership than any conventional weapon.

119

Published: Dec 27, 2025