Shopping cart

Your cart empty!

Terms of use dolor sit amet consectetur, adipisicing elit. Recusandae provident ullam aperiam quo ad non corrupti sit vel quam repellat ipsa quod sed, repellendus adipisci, ducimus ea modi odio assumenda.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Sequi, cum esse possimus officiis amet ea voluptatibus libero! Dolorum assumenda esse, deserunt ipsum ad iusto! Praesentium error nobis tenetur at, quis nostrum facere excepturi architecto totam.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Inventore, soluta alias eaque modi ipsum sint iusto fugiat vero velit rerum.

Sequi, cum esse possimus officiis amet ea voluptatibus libero! Dolorum assumenda esse, deserunt ipsum ad iusto! Praesentium error nobis tenetur at, quis nostrum facere excepturi architecto totam.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Inventore, soluta alias eaque modi ipsum sint iusto fugiat vero velit rerum.

Dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Sequi, cum esse possimus officiis amet ea voluptatibus libero! Dolorum assumenda esse, deserunt ipsum ad iusto! Praesentium error nobis tenetur at, quis nostrum facere excepturi architecto totam.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Inventore, soluta alias eaque modi ipsum sint iusto fugiat vero velit rerum.

Sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Sequi, cum esse possimus officiis amet ea voluptatibus libero! Dolorum assumenda esse, deserunt ipsum ad iusto! Praesentium error nobis tenetur at, quis nostrum facere excepturi architecto totam.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Inventore, soluta alias eaque modi ipsum sint iusto fugiat vero velit rerum.

Do you agree to our terms? Sign up

In a significant breakthrough for space biology, mice that spent two weeks aboard China’s space station have safely returned to Earth and successfully given birth, offering rare insights into how microgravity affects mammalian reproduction.

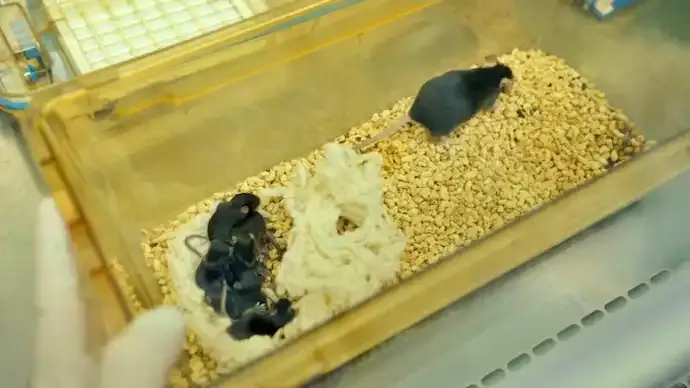

The experiment involved four mice sent to space on October 31 aboard the Shenzhou-21 mission. The animals were housed in a specially designed habitat aboard the Tiangong Space Station, engineered to replicate Earth-like conditions with regulated temperature, food supply and waste management.

Orbiting at an altitude of around 400 km until November 14, the mice were exposed to microgravity, space radiation and the station’s controlled environment before returning safely to Earth. After their return, one female mouse conceived naturally and gave birth to nine pups on December 10.

Six of the newborns survived — a rate considered normal for laboratory mice — with scientists observing healthy behaviour, regular nursing and no visible abnormalities. Researchers noted that this outcome contrasts with earlier space studies where rodents exposed to microgravity showed reduced fertility or developmental complications.

The China National Space Administration described the results as highly valuable for understanding how spaceflight affects embryos, foetal development and genetic stability. Such data is critical as space agencies worldwide assess the feasibility of long-duration human missions.

Previous rodent studies conducted on the International Space Station by NASA documented bone loss, muscle weakening and altered gene expression, but successful births from animals that had lived aboard a space station remain uncommon.

The newborn mice will now undergo detailed biological and genetic analysis to study how exposure to weightlessness influences cell division, immune responses and organ development during early life stages. Scientists believe this information could help develop protective strategies for astronauts on future Moon and Mars missions.

While mice are not direct substitutes for humans, their biological similarities make them important indicators for studying reproductive health in space. No abnormalities were detected during the mice’s time aboard Tiangong, suggesting the habitat functioned as intended, though deeper genetic findings are still awaited.

The experiment adds momentum to China’s expanding space programme, which includes long-term plans for lunar exploration and a future Moon base. As ambitions shift toward extended human presence beyond Earth, the success of these mice highlights the importance of understanding how life adapts beyond our planet.

84

Published: Dec 29, 2025